Lai Mohammed’s Blind Befence

A little over one-and-a-half years to the end of his second and final term in office, President Muhammadu Buhari gave his presidency a shot in the arm by sacking two of his ministers, Mohammed Sabo Nanono of Agriculture ministry and Saleh Mamman of the Power ministry. The sackings were generally unexpected, and seemed to portray the president as firm, in control of his presidency, and eager to do definitively more in the weeks and months ahead. He had talked tough a few weeks ago, at least as echoed by his National Security Adviser (NSA), Babagana Monguno, who quoted the president as charging his security chiefs to rein in banditry and insurgency or suffer being shuffled into retirement. Last week’s cabinet reshuffle would seem to indicate finally that the president knows what he wants from his administration, and more, how to get it. After all, he had also recently declared that his administration would not end a failure.

Most Nigerians will, however, remain skeptical that the president can still save the day or his presidency, despite his stimulating declaration that he shuffled his cabinet to strengthen the chain that holds his administration together. His government had done a review, he suggested, and the review had exposed the affected ministers’ shortcomings, adding stirringly that “These significant review steps have helped to identify and strengthen weak areas, close gaps, build cohesion and synergy in governance, manage the economy and improve the delivery of public good to Nigerians.” It is evident that for about six years, his presidency had been lethargic, indecisive, and seemed poised to mummify in chaos as his tenure neared its end. But if what ailed his presidency were consistent with the reasons he gave for the reshuffle, this shot in the arm may in fact be the appropriate and helpful anodyne to a faltering administration.

However, what is at the root of public disenchantment against his administration are weightier than he has seemed to recognise, and even more nuanced than his cantankerous and vituperative aides and cabinet members have consistently adduced. It is true that the administration was lethargic for all of six years or so, either as a consequence of his struggle with poor health or the cabalistic stalemate his presidency had had to endure for some years. Perhaps now, there seems to be some clarity around him, and he seems to know whom and whose judgement to trust and infuse into public policy. The public can only guess. But what is even truer is that what really ail his administration are more fundamental than any of his close aides lends credence to, to wit, the religious and ethnic veneer that coats his policies, the lack of philosophical rigour that suffuses his administration but which is necessary to define and animate the country’s future and vision, and the absolute absence of a conceptual understanding of what Nigeria, the most populous black nation on earth, is and must represent.

It is undeniable that the Buhari administration struggles with a lack of ideological direction, despite the vaunted, but now repudiated, progressivism of the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC). The administration is sometimes eclectic, seeming even to rely on the personal touch and efforts of some of the ministers, particularly Rotimi Amaechi and Babatunde Fashola; but even that eclecticism has often been corrupted and weakened by both the deliberate subversion of Nigeria’s secular constitution as championed by the likes of Communications minister Isa Pantami and the attenuated war against insurgency and banditry led by the security agencies. Few Nigerians now believe that President Buhari can remedy the problem in 20 months, regardless of how animated his actions and speeches are. They find it inexplicable that he still talks of grazing routes in the face of clear evidence of the destructive activities of herdsmen, most of them foreign mercenaries without cattle, and in the face of a clear lack of constitutional support.

It was in the midst of this confusion that Information minister Lai Mohammed, speaking in Cape Verde last week during the 64th Conference of the UN World Tourism Organisation Commission for Africa, trained his guns on Nigeria’s political and religious leaders as well as opinion moulders whom he accused of incitement and lack of patriotism. These inciters, Mr Mohammed argues, are the problem with the country. He voices his displeasure fairly exhaustively. Hear him: “In the last few weeks, the country has been awash, especially from the broadcast media, with very incendiary rhetoric which has created a sort of panic in Nigeria. The incendiary rhetoric that comes from political, religious leaders and some opinion moulders have the capacity to set the country on fire. This is because the rhetoric is pitting one ethnic group and religion against the other and overheating the polity. Our serious counsel to stakeholders is that they should understand and remember that leadership comes with a lot of responsibilities, tone down the hateful rhetoric because they are harmful to the country. They should remember that every war is preceded by these kinds of mindless rhetoric, especially when it comes from otherwise responsible people who the people have the tendency to take seriously.”

He, however, grudgingly concedes some points to the opinion moulders whose patriotism he questions: “We agree that there are challenges but the government is doing its best in addressing insecurity, banditry, insurrections, and fixing the economy. What one expected from these leaders at this trying period is support and encouragement. It is, however, quite disturbing that they have thrown caution to the wind and it is no longer about leadership and maturity but about who can say something that can break this country… If what they are praying for happens, they will no longer be leaders but servants in other countries.”

Mr Mohammed’s umbrage exemplifies the Buhari administration’s inability to grasp the country’s fundamental problem. He tries to redefine the problem in terms of weak ministerial links imperiling the strength of the chain. But Mr Mohammed’s conclusions are questionable. Though an information man himself, and a lawyer to boot, not to say a propagandist who profited from the liberal atmosphere enjoyed by the media under the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) presidency, he seems obscenely eager to eviscerate Nigeria’s broadcast media which is regulated by the authoritarian National Broadcasting Commission (NBC), an agency under the purview of the Information ministry. It is a clear indication that the APC does not have a media policy, is unable to appreciate how the media can be tweaked to project Nigeria’s continental power or dominance, and is totally oblivious that one day, the APC in opposition could be hoisted with its own petard.

Mr Mohammed blames religious and political leaders for incendiary rhetoric. He is parrying the truth. Has he explained what the so-called incendiary rhetoric is directed at? Is it not a reflection of how opinion leaders perceive the Buhari administration’s handling of ethnic and religious issues – the security appointments, the grazing brouhaha, the skewed response to retaliatory attacks on vicious and rampaging foreign Fulani militia, and all other public policies that portray the administration as prejudiced? Remove these provocations, item by item, and see whether there would be ‘incendiary rhetoric’. Before one person lost his life as a result of the self-determination agitations of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), the administration had hastily described the Southeast group as a terrorist organisation, and proscribed it. The world recognises Nigerian bandits and herdsmen as some of the worst terrorist organisations anywhere, but the administration has refused to declare them as such, even failing to attack them with the same vicious official rhetoric it directed against IPOB.

Mr Mohammed is dishonest not to understand that the rhetoric he complains against was triggered by the perception of the Buhari administration as lacking in impartiality. The incendiary rhetoric will continue despite his threats, until the administration recognises what Nigeria means, and until it evolves measures that would see the government responding to security threats with the impartiality Nigerians yearn for. The Information minister probably also knows, but won’t admit it, that public dismay at the administration’s failings has been influenced by the government’s refusal to take proactive measures to rein in insecurity, measures such as restructuring, which would in turn trigger a welter of salutary changes capable of dousing tension and placating rebellion. The country is on the verge of open rebellion, and the administration’s response has been desultory, incompetent, abusive, oppressive, and almost entirely counterproductive. Few Nigerians think anything substantial can be done in 20 months to mitigate the descent to chaos. It is left for the administration to prove them wrong, not to threaten and insult them. It is inconceivable that terrorism in the Northwest, aka banditry, cannot be reined in, except if it is true that the administration is not as altruistic as imagined. Governance is collapsing in the Northwest, schools are shut in many states in the North, and ethnic militias and kidnappers are running riot on the highways, with many travelers traumatised and turned to nervous wrecks. Nothing explains the slowness of the administration in identifying the factors responsible?

Mr Mohammed threatens and blackmails dissenters with the evil omen of war. He accuses the country’s opinion moulders of trying to instigate war whose consequences the critics could not hope to escape. But there is nothing in the positions of those who take issue with the Buhari administration that suggests they are pro-war. They may be disenchanted, angry and despondent, but they are not warmongers; they are merely responding to the acts of omission and commission of the administration, to its lethargy and indifference, to its refusal to be evenhanded. Of course should war break out, as experienced by many states in the North, it is not only Mr Mohammed’s hated rhetoricians that would be affected. The administration, not to say the country itself, could not hope to remain unaffected. There is so much at stake that it is frustrating and annoying the incoherence with which the administration has handled national crises. Abusing or arresting dissenters will not obviate the enormous tragedy unfurling over Nigeria, or mitigate the suspicion that the administration is promoting certain nefarious agenda.

When he sacked two ministers – the term cabinet reshuffle is inappropriate, for that implies that the leader is a coach – the president indicated he could act with resolve and dispassion. He gave added indication that if he extended that faculty to other areas of national life, peace, stability and growth could be engendered. But it remains only an indication. Without qualitative and multicultural and multireligious infusions into his kitchen cabinet, it is hard to sustain the optimism that somehow, the president can find the formula to retool and retune the country. It may be unfeeling to write him off, but even he must admit that time is not on his side, notwithstanding Mr Mohammed’s propagandist predilection for blindly defending the administration’s policies.

Obasanjo’s measurement of war and peace

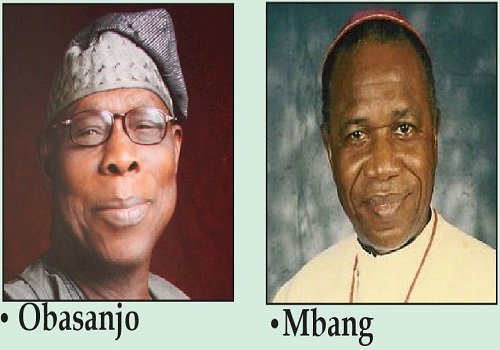

War and peace are two sides of the same coin. Strangely, the distance between the two is hardly perceptible. Flip the coin one way, and peace ensues; flip it the other way, and it is war. If it is understood that the distance is short, and the dividing line is wafer-thin, what of the costs then? Are they also indeterminate? No, glowed former president Olusegun Obasanjo, they are separated by a gulf, suggesting in addition that no matter what happens, it is always better to work for peace because it is cheaper than war. Speaking at a book launch and 85th birthday celebration of Prelate Sunday Mbang of the Methodist Church, Nigeria, the ex-president had propounded an intriguing costing for war and peace. In lionising the prelate as an exponent of unity, peace, security and progress, Chief Obasanjo had gushed: “I know that these are things that are dear to his heart. We want to assure you that Nigeria will continue to exist because the cost for Nigeria not to continue to exist is much more than the cost for us to make Nigeria to continue to exist.”

But measuring peace is fraught with a lot of difficulties. It is neither as straightforward as Chief Obasanjo puts it nor its metrics as easy and neat to calculate. To gain peace, sometimes war may be inevitable, especially if war, under any guise, is foisted on a people. Germany’s Adolf Hitler foisted World War II on the world, citing iniquitous World War I peace treaties. War was ineluctable. Of course, for the allies, war was far cheaper than the burden of slavery or occupation. As United States general and former president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, quipped, “…A soldier’s pack is not so heavy as a prisoner’s chains.” Chief Obasanjo is right to desire peace in place of war, giving his experience fighting one. But when gross inequity permeates a political system, and a people are in danger of being enslaved, fighting becomes a duty, and its cost infinitely more tolerable.

Nigerian leaders sentimentalise war. War will always be fought, for no political system, especially one built on injustice and unfairness, can last for all time. Even those built on justice sometimes fail, as past empires and kingdoms have shown. Nigeria is an impermanent arrangement, a hodgepodge its leaders have been reluctant or incompetent to remake to engender stability and equilibrium. Political and religious leaders say the country is not an accident, but was put together by God for a purpose. Can they tell whether that purpose has not lapsed, as it lapsed for past empires and alliances? After decades of fractious relationship, culminating in the near-war situation of today, should Nigerian leaders not seek ways of realigning the country along just and enduring lines instead of promoting dissension and ethnic and religious superiority?

Regardless of Europe’s advanced economies and civic cultures, not to talk of those of Asia and America, wars will still be fought on some apocalyptic tomorrow. Wars are a permanent feature of humanity, whether they are cruel and costly or not, and a student of warfare like Chief Obasanjo should know. Fighting or desiring war is not a question of cost or of the grief that accompanies it, or whether it is lost or won; it is a question of every generation doing its best to avoid it until it becomes inevitable. Germany lost nearly a generation in both the 1914-1918 and 1939-1945 wars, with its elite humiliated by defeat and the savagery that defined the bloodletting. For the sake of ideological ascendancy, China and Russia each lost nearly as many people as Germany lost in its wars; but all of them alike have recovered and developed political, social and economic systems that attract millions of immigrants. In future, they will fight more wars, costly or cheap, noble or ignoble. It was, therefore, not expected of Chief Obasanjo to be squeamish about war despite its tragic concomitants; instead, he should campaign for justice and equity, without which war would be inevitable.

TH NATION

Please, remember to always like our page and visit our website for updates

TSOEDE TV

TSOEDE TV